After a few months with PICO-8 and Lua, I grew to appreciate the simplicity of its independent update() and draw() loop. However, I also found myself constrained by the fantasy console’s limitations—a 64kb OS, a language prone to off-by-one errors, and a sparse package ecosystem. For example, while most modern languages have several Entity Component System (ECS) libraries to choose from, PICO-8 has just one. I wanted to find a framework that offered the same creative freedom without the technical constraints.

My search led me to Ebitengine, a game engine for Go, which I discovered through a GameFromScratch video. Having been interested in learning Go or Rust, I decided to dive in. I completed the Tour of Go in my spare time and was immediately hooked.

While Go isn’t the most common choice for game development, its strengths in backend systems, concurrency, and performance are highly relevant to my interests. The language introduces features that feel like a breath of fresh air. For instance, formatting is standardized with a single command: gofmt -w .. This is a welcome change from the world of JavaScript, where I constantly wrestled with competing linters and style configs. Go’s package system also encourages clean project organization from the start. In the past, I’d often create a monolithic main file with a messy src directory. While using an ECS architecture provides some structure, Go’s packages make it intuitive to group related logic into clean, separate modules.

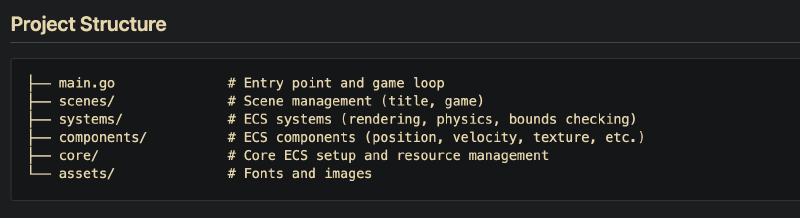

This bouncing DVD logo demo, while simple on the surface, is intentionally over-engineered to serve as a template and learning exercise. I implemented a scene manager using Go’s interfaces, defining Update, Draw, Enter, and Exit methods to handle game states and resource management. Integrating libraries is also a breeze. For the ECS, I used Ark, a flexible library designed for high-performance simulations. A key feature I appreciate is the ability to run queries outside of systems, which is a limitation I found in other libraries like bitecs. This allows for a more flexible, event-driven approach without managing state flags every frame.

The result is a clean, organized project structure that feels scalable. I can navigate the file hierarchy without feeling overwhelmed, and the combination of Go and Ebitengine gives me the confidence to tackle more ambitious projects, from a massive game to a small weekend game jam tool.

I hope this write-up proves useful to others exploring game development in Go.